Hello, this is Miyanouchi from Relative. Thank you as always for reading my blog.

Over the three-day weekend in October, I went back to my hometown—Matsushiro in Nagano City, Nagano Prefecture. The main reason was to visit my family’s graves, but it turned out to be a beautiful little trip. The weather was clear and crisp, the perfect kind of autumn day.

Matsushiro is a charming castle town that was once ruled by the Sanada clan during the Edo period. Many people might think of Sanada Nobushige—better known by his popular name, Yukimura Sanada—when they hear that name. The town still has Matsushiro Castle and relaxing hot springs, giving it a wonderful mix of history and atmosphere.

At the cemetery rests my mother. She passed away at a young age and went to heaven far too soon.

Now that I’ve lived beyond the age she reached, I truly feel how young she was when she left this world. That’s why I want to make each day the best it can be and keep moving forward in life.

After the memorial service, I went to the hot springs with my family. Matsushiro Onsen is a favorite spot among locals, and for good reason.

The water there is a beautiful golden color. It’s actually clear when it first gushes out, but once it’s exposed to the air, it gradually turns golden.

The spring water is rich in iron, slightly salty, and has that wonderful cloudy texture that hot-spring lovers can’t get enough of. If you’re a fan of cloudy hot springs too, I’d love to share stories and exchange recommendations!

On the way back on the Shinkansen, I took some time to do a bit of reading. I often support client companies, both foreign and Japanese, and while I understand pieces of their different HR and evaluation systems, I’ve realized I haven’t fully put the whole picture together yet.

So this time, I decided to dedicate some moments to deepen my understanding of the differences between overseas and Japanese systems. I was reading a book called Designing the Personnel System : A Guide to Moving Away from the Japanese-Style Employment System.

The terms “moving away from the Japanese-style employment,” “remote work,” “flex time,” and “job-based employment” have been talked about for quite a while now. This book offers a clear and easy-to-understand summary of the differences between Western and Japanese HR systems, and the distinct ways people in these regions think about work.

Here are some parts that really stood out to me from the book:

“What Determines a Salary?”

The author uses a simple example from a language school.

There are two teachers:

One is American and only speaks English. The other is a British person of German descent who speaks both English and German.

Who do you think earns the higher hourly wage?

In Japan, many people say the bilingual teacher would earn more. But outside Japan, that’s usually not the case.

This difference stems from the distinction between job-based and ability-based pay systems. In Japan, salaries are based on a person’s abilities, whereas in Western countries, salaries are determined by the job itself, regardless of the number of languages spoken.

If the work is the same, the pay is the same—whether someone speaks one or two languages. In other words, pay is tied to the job, not the individual.

Also, while Japanese companies may mix job titles within the same pay grade, foreign firms with formalized positions keep job titles separate within the same grade.

(From 『Designing the Personnel System』)

The book also touches on

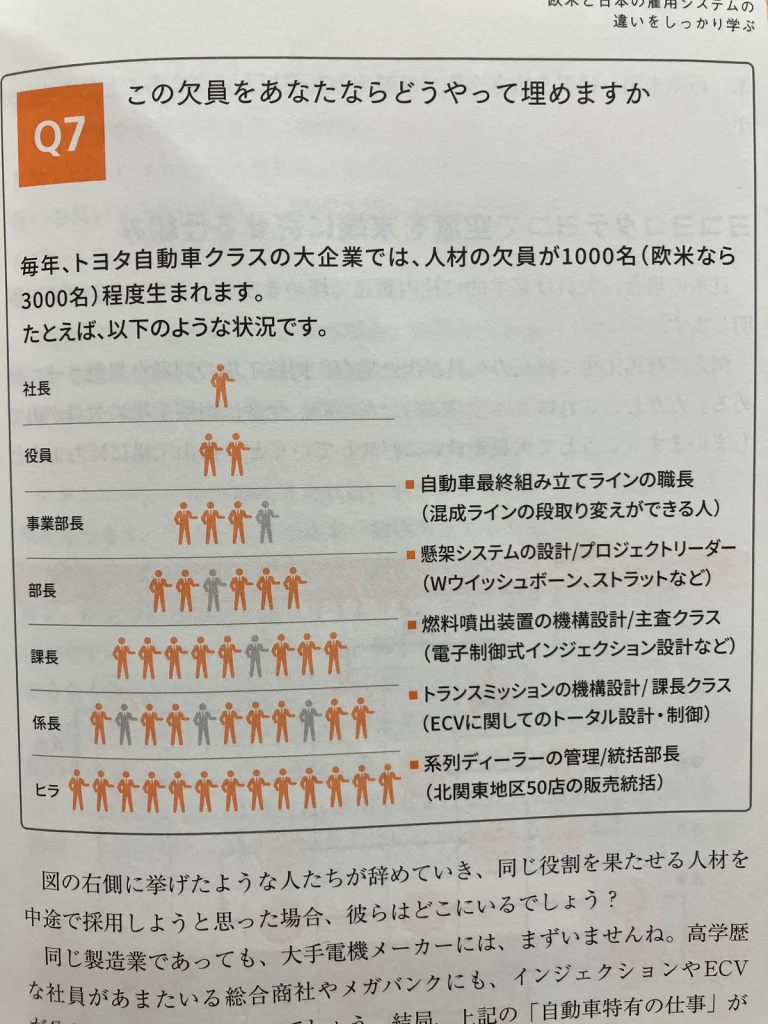

why Japan’s practice of mass hiring of new graduates persists, while Western companies mainly hire mid-career professionals. It discusses how even very stable large firms like Toyota and Nissan see hundreds to thousands of retirements annually, mostly predictable by department, making workforce replenishment manageable.

When trying to replace specialized workers with mid-career hires, it’s not easy to find replacements outside very specific rival companies or contractors. So, the competition for experienced hires tends to be within the same industry, creating a constant tug-of-war for talent.

“The System for Moving Vacant Positions to the Edges Horizontally and Vertically”

In Japan, vacancies are usually filled from within the company. Here’s how this system works:

For example, if a section manager position opens up at the Gunma factory, someone holding the same position at the Okazaki factory will be transferred to fill the gap. But this doesn’t solve the problem completely — it just moves the vacancy to Okazaki. When the vacancy gets passed sideways like this, sometimes at the Koriyama factory, there will be someone ready to be promoted from assistant manager to section manager.

When that person is promoted, the vacancy moves down one level to the assistant manager position. Then it gets passed sideways again, moving in a kind of chain reaction. This bumping effect moves vacancies sideways and sometimes vertically, always ending up pushed out to the very edges.

Vacancies get passed horizontally and vertically until they finally accumulate at the very bottom of the organization. That’s how a large number of entry-level vacancies tend to occur.

(Excerpt from 『Designing the Personnel System』)

There are significant differences in personnel systems and evaluation methods between foreign-affiliated and Japanese companies. Each has its strengths and weaknesses, and it’s important to understand these differences not as better or worse, but as differences in philosophy and culture.

I have a deep respect for HR professionals who strive to find the best solutions within their own cultural and value frameworks.

If you have any questions about hiring or career changes, please feel free to reach out. Whether you’re active in a high-end brand or considering your next challenge in this industry, or if you’re a company thinking about recruitment, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

📩 Contact us here:

https://hr.relative.company/contact/